TABLE OF CONTENTS

Arthritis is a group of conditions that causes chronic damage to the joints of the body particularly the hips and the knees. Years ago, arthritis was largely akin to old age. However, nowadays, anyone can become afflicted with this chronic condition, even children (juvenile arthritis). Nonetheless, most arthritic conditions usually increase with age, with the most common type being Osteoarthritis, which is age-related and Rheumatoid arthritis, one of the most severe types (Silman and Hoch-berg, 1994). Some of the clinical signs of arthritis include pain, reduced range of motion, inflammation as well as deformity (Malemud et al. 2003).

While there is no ‘definitive cure’ for arthritis, doctors are finding novel ways of treating and managing the condition. To this extent, more research is being conducted on plants and food in general, most of which were once considered ‘anecdotal’ to now finding some scientific merit. One such is ‘pine bark extract’ or pycnogenol, which is the antioxidant that is found in the bark as well as the name under which the product is typically marketed.

pine bark extract is derived from the bark of the Landes or French maritime pine tree (Pinus maritime). This particular tree is a member of the Pinaceae family which includes other well-known species such as cedars (Cedrus), pine (Pinus) and spruce (Picea) etc. (Britannica.com). The bark extract is famed for its antioxidant properties which are touted to be effective for healing as well as treating and preventing particular conditions. However, can it help with arthritis). Let’s discuss!

The Discussion

Pine Bark extract is a supplement that is used worldwide for its many purported benefits. Usually, you will find the extract under the name, pycnogenol, which is the patent under which it is sold. Pycnogenol is the standardized extract from the bark and the marketed name of the supplement. These compounds have a high concentration of polyphenols which include catechins and phenol acids (Iravani and Zolfaghari, 2011; Blazso et. al. 1994; Rohdewald, 2002). The polyphenols in this bark are said to make up about 60-75% of its nutritional properties (Rohdewald, 2002). These potent compounds have been widely studied due to their anti-inflammatory and high-antioxidant activities (Iravani and Zolfaghari, 2011).

Several studies have outlined the purported benefits of these compounds, for example, catechins, which are also plentiful in green tea, are touted to help manage body fat as well as reduce low-density lipoproteins (LDL) cholesterol. Catechin may also be able to prevent as well as manage some other lifestyle diseases (Nagao et. al. 2005). Pine bark is also known for its flavonols and bioflavonoids, properties that are usually found in fruits and vegetables, particularly leafy greens.

The benefits of its flavonols and bioflavonoid properties were foretold in a story that dates back to a Four Hundred and Fifty (450) years old story of an event that took place in 1534. The story highlighted what happened when a ship carrying the French explorer – Jacques Carter and his crew became stranded at sea. The men then became ill with Scurvy, a disease that is caused by a severe deficiency of vitamin C. Scurvy can become fatal if not treated.

The crew was instructed to brew a concoction of the pine bark and its needles by Quebec Indians, as the ship was docked in Quebec Canada. The brew worked. Many years later, research contends that the flavonols in the bark acted like antioxidants and increased the effectiveness of vitamin C which is prominently found in the needles of the pine tree (Encyclopedia.com).

For this reason, the antioxidants in pine bark have been grouped as oligomeric proanthocyanidins or OPCs. These antioxidants are said to be able to reduce cholesterol and thus incidences of heart disease as well as strengthen the body’s collagen production abilities. They are also said to be able to reduce plaque buildup which can damage the arteries in the long term. As such, pycnogenol is usually used to treat cholesterol issues, circulation, edema and varicose veins. It is also used to manage symptoms of premenstrual syndrome (PMS), menopause, arthritis and general inflammation in the body (Encyclopedia.com).

In this article, we will be looking at the research surrounding its benefits for arthritic conditions, particularly Osteoarthritis and Rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatoid arthritis has been reported as one of the most severe types of the condition (Silman and Hoch-berg, 1994) while osteoarthritis, is the most common type of arthritis.

You can read more on arthritis as well as foods that may help with its management in this arthritis EBook:

Pine Bark Arthritis Benefits:

- Rheumatoid Arthritis

- Osteoarthritis

Pine Bark Extract and Rheumatoid Arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis is a condition that is said to be caused by both systemic and local inflammation in the body, particularly in areas like the joints of the knees, hence its distinction as an inflammatory disease (Firestein, 2001). The disease is said to affect about one (1%) percent of the adult population, globally (Firestein, 2001). According to (Firestein, 2001), Rheumatoid arthritis is an inflammatory disease that can destroy the cartilage of the bones.

As such, this condition is a painful one and will thus cause sufferers to always seek ways to manage it, seeing that research has contended that there is no known cure. A few drugs are usually prescribed to manage the pain associated with the condition such as disease-modifying anti-rheumatoid drugs (DMARDs) and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). DMARDs are usually provided to patients to manage its debilitating effects on the immune system (Shiokawa et. al. 1984; Yasuda et. al. 1994), while NSAIDs are usually used to provide both therapeutic effects and pain relief (Schuna and Megeff, 2000).

However, with all drugs, there are associated unwanted side effects such as gastric toxicity among others while not showing any positive effects on the lesions of the joints for more sustained effects (Santana-Sabagun and Weisman, 2001). To this extent, researchers have been exploring other means to help suffers from the condition to better manage it. One such is – Pine bark extract or ‘pycnogenol’ as it is widely known.

One of the revered compounds of pine bark is Flavangenol (FG). Flavangenol (FG) is an extract of pine bark which mostly comprises powerful water-soluble polyphenols such as oligomeric, and proanthocyanidins (OPCs) (Ikeguchi et. al, 2006). Flavangenol (FG) is also one of the registered trademarks of a pine bark marketed product. These polyphenols which are high in antioxidants include catechins and epicatechin (Ikeguchi et. al, 2006) and can be found in foods such as grapes, cranberries, apples, green tea (most teas in general), as well as in pears and red wine (Hellstrom and Mattila, 2008). Research has shown that the antioxidants found in the polyphenols were able to either prevent or reduce atherosclerosis (Sato et. al. 2009). It was also found to positively impact diabetes (Kamuren et. al. 2006; Maritim et. al. 2003) as well as hypertension (Liu X, et. al. 2004).

The effects of FG on rheumatoid arthritis were observed in a Four (4) week study with collagen-induced arthritis rats. Flavamgenol was used with the infamous pain medication, ibuprofen. The FG used contained 72.5% polyphenols, with 2.98% catechins. The rats were placed in Three (3) groups- a control group (0.3%) FG, a 1% FG group and a 0.05% Ibuprofen group (Tsubata et. al. 2011). Each of the groups had a total of Eight (8) rats. There was also a non-induced group or a normal group. This group was fed a standard diet, while the control groups were fed an FG standardized diet or an ibuprofen-containing standard diet.

The results showed that FG suppressed the progression of collagen-induced arthritis in rats, by preventing acute and chronic inflammatory lesions. However, this was only observed in the rats that were fed the one (1%) percent FG diet and not those of the 0.3% FG diet. Additionally, the result showed that the 0.05% ibuprofen-containing diet rats, suppressed cartilage degeneration and periostitis.

While the researchers contended that the degree of impact between the two experiments will be dependent on the degree of cartilage damage to the knees, FG can still be viewed as a safe and novel substance for the treatment and management of rheumatoid arthritis in humans, not negating further research.

Pine Bark Extract and Osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis is also an arthritic condition like rheumatoid arthritis. However, this is said to affect mostly the joints of the knees and hips. While these arthritic conditions can affect persons of any age, osteoarthritis is said to be a disease that predominantly affects the elderly, as it progresses with age (Rohdewald, 2018).

Some of the symptoms that are associated with this disease include pain and reduced mobility of the joints (Rohdewald, 2018). These symptoms are usually caused by inflammation which then gives rise to pain (Matthiessen and Conaghan, 2017). While hyaluronic acid and glucosamine are sometimes used to supplement the damage done to the cartilage, NSAIDs are typically prescribed to manage localized inflammation and pain (Rohdewald, 2018).

However, with pharmaceutical drugs, long-term side effects come into play, which according to research can lead to gastrointestinal injuries such as bleeding and perforation in the intestinal tract as well as peptic ulcers (Gooch et. al. 2007). Additionally, high doses of NSAIDs, according to reports, may lead to kidney failure as well as an increase in one’s blood pressure (Gooch et. al. 2007; Snowden and Nelson, 2011). As such, pine bark standardized extract in the form of pycnogenol is being researched as a safe alternative, especially over the long term (Snowden and Nelson, 2011).

According to research, pycnogenol behaves like a sustained release of active compounds that can help with pain relief as well as possess anti-inflammatory actions (Rohdewald, 2018) without unwanted side effects. According to (Rohdewald, 2018), the sustaining effects of pine bark extract on the body are due to its diverse anti-inflammatory properties and its metabolism in the bloodstream. A study by (Canali et. al. 2009) found that its anti-inflammatory substances such as catechins, ferulic acid and caffeic acid were found in blood plasma Thirty (30) minutes after consumption with larger concentrations observed between One (1) and Four (4) hours after consumption. Additionally, ferulic acid was found in the patient’s urine up to 25 hours after ingestion (Canali et. al. 2009).

The positive effects of pycnogenol on arthritis were also observed in three (3) clinical published studies (Belcaro et. al. 2008, Farid et. al. 2007; Cisar et. al. 2008). These studies were all randomized, double-blinded and a controlled placebo group. The participants comprise patients between the ages of Forty-eight (48) to Fifty-four (54) years of age, who were suffering from mild Osteoarthritis at either stage 1 or 2.

The patients were administered fifty (50mg) milligrams of pycnogenol to be taken three (3) times daily or a placebo. The patients were also able to take NSAIDS as needed. In the first study of Thirty-five (35) volunteers, they reportedly experienced a reduction in pain (-45%), and stiffness as well as saw improvement in their physical performance due to the improvement in their well-being (Belcaro et al. 2008). The second study, which was a bit larger, had One Hundred (100) participants. These participants took One Hundred and Fifty (150mg/day) milligrams of pycnogenol per day.

The participants also reportedly experienced a reduction in pain and stiffness as well as an improvement in their physical performance by up to 22% (Cisar et al. 24). Finally, the third study, which had over One Hundred and Fifty-six (156) participants who also administered One Hundred and Fifty (150 mg/day) milligrams of pycnogenol also experienced a reduction in pain and stiffness, with a significant improvement in physical functions of up to 52%. These results were not the same for the placebo group which usually had no effect in all three (3) studies (Farid et. al. 23).

All three (3) studies demonstrated the significant impact pycnogenol can have on the symptoms of Osteoarthritis even with the reduced intake of NSAIDs. Additionally, the participants did not report any adverse effects with pycnogenol and even reported reduced or mild unwanted effects of the NSAIDs such as headache, dizziness and gastric issues.

You can read more on arthritis as well as foods that may help with the management of arthritis in this EBook:

EBook – My Little Fingers (A Book on Arthritis) – Science Simplified + Natural ways to manage it!

Side Effects of Pycnogenol

Pycnogenol is reportedly generally safe, with no dangerous side effects observed. Some noted side effects include headaches, dizziness, nausea, sleepiness and even skin irritation. These side effects were noted to have been mild in a clinical trial with over seven thousand (7,000) patients (Rohdewald, P. (2015). However, one should seek guidance before embarking on a supplement regimen, especially if you are on medications. Additionally, the safety of the ingredient has not been established for pregnant, lactating women and children. As such, persons who fall into this category should simply avoid it.

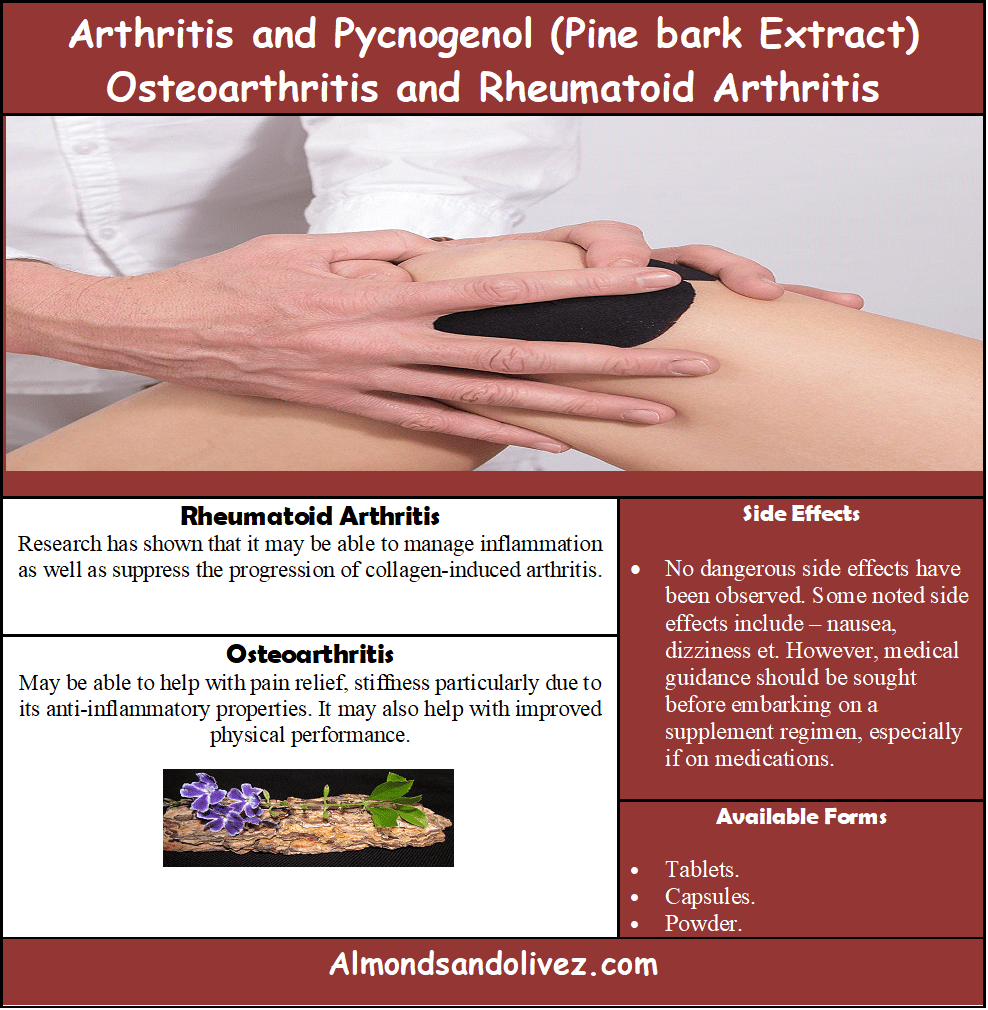

Illustrative Summary

Here is a summary of the effects of Pine Bark Extract on Rheumatoid Arthritis and Osteoarthritis.

Let’s Sum Up!

The research on arthritis has been advancing over the years, with scientists investigating more ways, outside of prescription, to manage or treat the condition. One such is pine bark extract, particularly, its standardized formulation – pycnogenol, which is the patented marketed name of the product.

Pycnogenol has been shown to be beneficial to arthritic patients, particularly those suffering from rheumatoid and osteoarthritis. According to research, it may be able to reduce pain, stiffness and improve physical performance and thus improving the overall well-being of arthritis patients.

While more research is still warranted to truly confirm the beneficial effects of pine bark on an even broader scale, these studies do provide a ray of hope for millions of people who are battling the condition, mild or severe. Have you used pine bark extract or pycnogenol before? What did you use it for? How was it? Share it with us nuh!

You can also check out these other posts on foods that can reportedly help with fighting inflammation in the body and as such, arthritis:

- Cherry O’ Baby – Five (5) Health Benefits of Eating Cherries!

- Magnesium – The quality sleep enhancer plus Four (4) more benefits worth knowing!

- Moringa – Nature’s Multivitamin without a Bottle – Here are Five (5) Researched Reasons Why!

- Pycnogenol and Diabetes – Is there a positive link?

Editor’s Note: Article updated on July 9, 2024.

- Belcaro G, Cesarone MR, Errichi S, et al.: Treatment of osteoarthritis with Pycnogenol_. The SVOS (San Valentino Osteoarthritis Study). Evaluation of signs, symptoms, physical performance and vascular aspects. Phytother Res 2008;22:518–523.

- Blazso G, Gabor M, Sibbel R, Rohdewald P. An anti-inflammatory and superoxide radical scavenging activities of a procyanidins containing extract from the bark of Pinus pinaster sol. and its fractions. Pharm Parmacol Lett. 1994;3:217–220.[Google Scholar]

- Canali R, Comitato R, Schonlau F, et al.: The anti-inflammatory pharmacology of Pycnogenol in humans involves COX-2 and 5- LOX mRNA expression in leukocytes. Int Immunopharmacol 2009;9:1145–1149.

- Cisar P, Jany R, Waczulikova I, et al.: Effect of pine bark extract (Pycnogenol_) on symptoms of knee osteoarthritis. Phytother Res 2008;22:1087–1092.

- Farid R, Mirfeizi Z, Mirheidari M, et al.: Pycnogenol supplementation reduces pain and stiffness and improves physicalfunction in adults with knee arthritis. Nutr Res 2007;27:692–697.

- Firestein GS. 2001. Etiology and pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. In: Kelly’s Textbook of Rheumatology

- (Ruddy S, Harris JED, Sledge CB, Budd RC, Sergent JS, eds), Vol 2, p 921–926. WB Saunders, Philadelphia.

- Gooch K, Culleton BF, Manns BJ, et al.: NSAID use and progression of chronic kidney disease. Am J Med 2007;120: 280.e1–e7.

- Hellstrom JK, Mattila PH. 2008. HPLC determination of extractable and unextractable proanthocyanidins in

- plant materials. J Agric Food Chem 56: 7617–7624.

- Ikeguchi M, Tsubata M, Tabata A, Takagaki K. 2006. Effects of pine bark extract on lipid metabolism in rats. J

- Jpn Soc Nutr Food Sci 59: 89–95.

- Iravani S, Zolfaghari B. Pharmaceutical and nutraceutical effects of Pinus pinasterbark extract. Res Pharm Sci. 2011;6:1–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamuren ZT, McPeek RA, Watkins JB. 2006. Effects of low-carbohydrate diet and Pycnogenol treatment on

- retinal antioxidant enzymes in normal and diabetic rats. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther 22: 10–18.

- Liu X, Wei J, Fengsen T, Shengming Z, Wurthwein G, Rohdewald P. 2004. Pycnogenol, French maritime pine

- bark extract, improves entothelial function of hypertensive patients. Life Sci 74: 855–862.

- Malemud CJ, Islam N, Haqqi TM. 2003. Pathophysiological mechanisms in osteoarthritis lead to novel therapeutic strategies. Cells Tissues Organs 174: 34–48.

- Maritim A, Dene BA, Sanders RA, Watkins JB. 2003. Effects of Pycnogenol treatment on oxidative stress in

- streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J Biochem Mol Toxicol 17: 193–199.

- Mathiessen A, Conaghan PG: Synovitis in osteoarthritis: Current understanding with therapeutic implications. Arthritis Res Ther 2017;19:18.

- Nagao T, Komine Y, Soga S, Meguro S, Hase T, Tanaka Y, et al. Ingestion of a tea rich in catechins leads to a reduction in body fat and malondialdehyde-modified LDL in men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:122–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nenonen MT, Helve TA, Rauma AL, Hänninen OO. Uncooked, lactobacilli-rich, vegan food and rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol. 1998 Mar;37(3):274-81. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/37.3.274. PMID: 9566667.

- Rohdewald P. A review of the French maritime pine bark extract (Pycnogenol), a herbal medication with a diverse clinical pharmacology. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2002;40:158–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar].

- Rohdewald P: Update on the clinical pharmacology of Pycnogenol®. Med Res Arch 2015;3:1–11 [Google Scholar].

- Rohdewald PJ. Review on Sustained Relief of Osteoarthritis Symptoms with a Proprietary Extract from Pine Bark, Pycnogenol. J Med Food. 2018 Jan;21(1):1-4. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2017.0015. Epub 2017 Aug 24. PMID: 28836883; PMCID: PMC5775113.

- Santana-Sabagun E, Weisman MH. 2001. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. In: Kelly’s Textbook of Rheumatology (Ruddy S, Harris JED, Sledge CB, Budd RC, Sergent JS, eds), Vol 1, p 799–822. WB Saunders, Philadelphia.

- Sato M, Yamada Y, Matsuoka H, Nakashima S, Kamiya T, Ikeguchi M, Imaizumi K. 2009. Dietary pine bark extract reduces atherosclerotic lesion development in male ApoE-deficient mice by lowering the serum cholesterol level. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 73: 1314–1317.

- Schuna AA, Megeff C. 2000. New drugs for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Health Syst Pharm 57: 225–234.

- Shiokawa Y, Horiuchi Y, Mizushima Y, Kageyama T, Shichikawa K, Ofuji T, Honma M, Yoshizawa H, Abe C, Ogawa N. 1984. A multicenter double-blind controlled study of lobenzarit, a novel immunomodulator, in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 11: 615–623.

- Silman, A. J.; and Hochberg, M. C. Epidemiology of the Rheumatic Diseases. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994.

- Snowden S, Nelson R: The effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on blood pressure in hypertensive patients. Cardiol Rev 2011;19:184–191.

- Tsubata M, Takagaki K, Hirano S, Iwatani K, Abe C. Effects of flavangenol, an extract of French maritime pine bark on collagen-induced arthritis in rats. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo). 2011;57(3):251-7. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.57.251. PMID: 21908949.

- Yasuda M, Nonaka S, Wada T, Yamamoto M, Shiokawa S, Suenaga Y, Nobunaga M. 1994. Additive two DMARD therapy of the patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol 13: 446–454.