TABLE OF CONTENTS

Cranberries are among the elite of berries and are even considered a premier fruit in many societal circles, largely due to their purported health benefits. As such, like other berries which include the famous blueberries, black, and raspberry, it is sought after and enjoyed in many cuisines and festivities, especially during the Christmas or ‘Yuletide’ season. But what makes this little red fruit an elite neighbour of the berries clan?

Well, according to research, cranberries contain antioxidants, which help the body fight free radicals and oxidative stress, situations, which if not controlled, can lead to the development of some of the most common debilitating diseases such as cancer, diabetes, and heart diseases.

Cranberries are also purported to contain other nutrients such as lutein, which is said to be excellent for eye health as well as calcium, folic acid, and omega-3 fatty acids. In this article, we are going to discuss some of the purported health benefits of this ‘likkle’ red, cherry-looking fruit, including its well-talked-about benefits on the urinary tract. Let’s discuss!

You can read more on vitamins and minerals here as well as on another type of berry, blueberry here.

- Our ABCs (Vitamins Overview)

- Blueberries – They are more than just for brain health – Here are 5 awesome benefits worth knowing!

The Discussion

Cranberry is labelled among three (3) of the most commonly cultivated fruits of North America even though it is said to be originally from New England (Zhao, 2018). Cranberries are enjoyed in many forms ranging from sauces to one of the most common – juices (cranberryinstitute.org & cabi.org). These little red berries form part of the Ericaceae family which includes other berries such as huckleberry and blueberries. The berry is naturally grown in acidic swamps in peat moss and in forests that are humid (Bruyere, 2006).

According to research, cranberries comprised Eighty-eight (88%) percent water, organic acids such as salicylate as well as fructose, flavonoids, vitamin C, anthocyanidins, and catechins (Guay, 2009). The unique taste of cranberry is attributed to the chemical constituents – iridoid glycosides (Guay, 2009). Iridoid glycosides are a group of compounds that are regarded as defence chemicals against herbivores and pathogens and generally have a bitter taste (sciencedirect.com).

While many of us would like to enjoy the juice in its pure form, research dictates that this ‘pure form’ which usually has a PH greater than Twenty-five (25) would be too acidic and unpalatable, even with the addition of sweeteners (Guay, 2009). As such, you might see inscribed on your purchased bottles of cranberry juice and cocktails such percentages as Twenty-five (25%) percent, Eighteen (18%) percent instead of One Hundred (100%) percent, etc., which signifies the amount of cranberry that make up that product.

However, cranberry cocktail drinks with about 25% cranberry are usually the general choice among women who are seeking to ward off UTIs (Hisano et al. 2012). Nonetheless, to enjoy most of its benefits, research recommends that the juice is consumed just before a meal or two (2) hours after. It is also recommended that one consume lots of water after consuming cranberry juices, especially, if it is prepared from dehydrated juices (Bruyere, 2006).

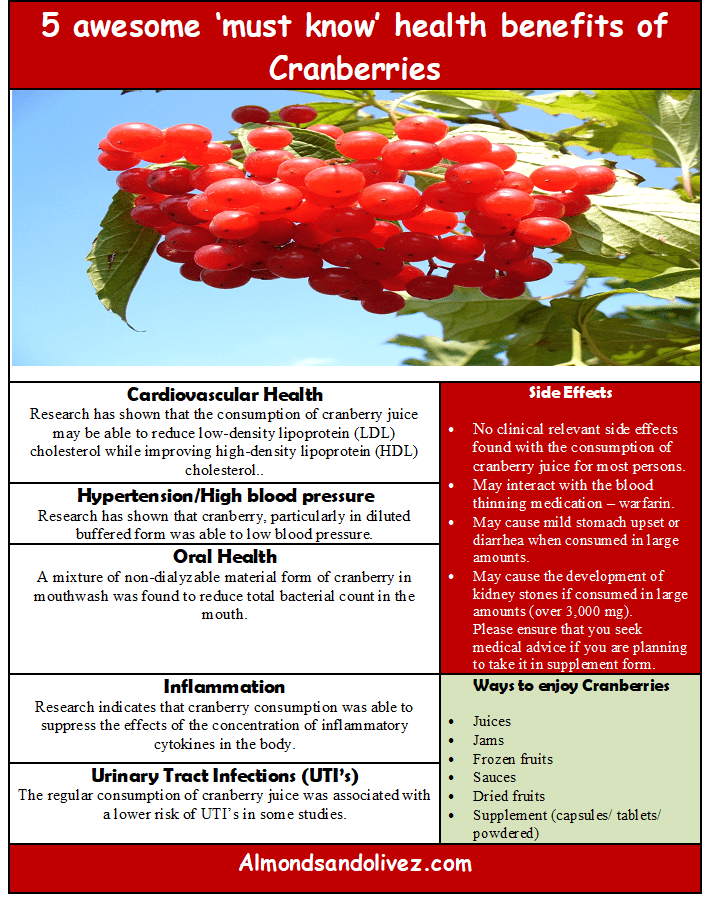

In this article, we will be exploring five (5) touted health benefits of cranberries. These benefits include its cardiovascular health possibilities, hypertension, its ability to fight inflammation, oral health, and the famous and most researched of the benefits, its possible effects on infections of the urinary tract (UTIs). We will also discuss any cautionary tale of consuming this famous little red berry.

Five(5) awesome ‘must know’ health benefits of Cranberries

- Cardiovascular health.

- Hypertension/High Blood pressure.

- Fighting inflammation.

- Oral health.

- Urinary tract infections (UTIs).

Cardiovascular Health and Cranberry

Research has shown that cranberry consumption accounts for a favourable effect on cardiovascular disease (CVD) due to its effects on some of the risk factors associated with cardiovascular issues. Some of these issues include dyslipidemia, inflammation, hypertension, and arterial stiffness among others (Blumberg et al., 2013). Dyslipidemia in the body occurs from a high level of cholesterol or triglycerides or both as well as low high-density lipoprotein (HDL), the ‘good’ cholesterol (merckmanuals.com).

In fact, both animal and human studies have cited that the consumption of cranberry juice has the potential to lower low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol (bad cholesterol) while increasing high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol (good cholesterol). This is due largely to cranberry’s ability to improve one’s lipid profile.

This was observed in a study conducted with a group of Syrian hamsters who were fed a diet that was high in fat (Kalgaonkar et al., 2010) This result was also equivalent to another study conducted with ovariectomized rats (Yung et al. 2013) as well as with swine with a condition known as hypercholesterolemia (Reed, 2002).

The results of these studies were also comparable to clinical studies of over One Hundred and Fifty (150) participants with hypercholesterolemia. The results showed that low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol was lowered while high-density lipoprotein (HDL) increased with the consumption of a purified mixture of anthocyanins of about Three Hundred and Twenty (320) mg/d (Zhu et al., 2013). Similar results were also observed in another population sample of obese men (Ruel et al. 2006) as well as with patients suffering from diabetes mellitus (Lee et. al., 2008).

While the aforementioned studies were done on humans with medical issues, some studies on healthy individuals or those with cardiovascular disease (CVD) did not show any significant effects of the consumption of cranberry juice on plasma lipids lipoprotein profile (Dohadwala et al. 2011; Flammer et. al, 2013 and Ruel et al. 2005 among others). Nonetheless, some researchers based these findings on discrepancies in the research samples, such as differences in the study population, their background as well as baseline lipid, and particular medications the sample population was taking at the time of the study.

Additionally, while the exact mechanism responsible for the improved lipoprotein profile after the consumption of cranberry bioactive is not fully understood by researchers, some studies have attributed these results to how the expression of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptors behave in the body, which would have course impact the level of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol Chu and Liu, 2005), which would be expected to lower concentration of plasma low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol.

Further, a study that consisted of individuals with dyslipidemia showed that the supplementation of anthocyanins inhibits cholesterol ester transfer protein (CETP) (Qin, 2009) which would in effect increase one’s high-density lipoprotein (HDL) and thus cause a reverse in the transport of cholesterol (Tall, 2007).

Hypertension and Cranberry

The research on the effects of cranberry juice consumption and hypertension has been favourable in some instances and inconclusive in others. However, there are researches with strong supporting data that have shown that the consumption of cranberry juice may have a positive effect on one’s blood pressure. One such study was conducted on anaesthetized rats with diluted buffered cranberry juice.

In this study that was conducted by Apostolidis et. al., (2006), it was shown that the diluted buffered cranberry juice, administered intravenously, was able to lower the blood pressure in the rats. Additionally, in a study by Kalgaonkar et. al. (2010) with Syrian hamsters, it was found that cranberry extract was able to prevent an increase in blood pressure even with the consumption of a diet high in fat.

Nonetheless, while the effects on blood pressure and cranberry juice effects were largely observable in animal studies, some clinical studies have failed to show any blood pressure-lowering effects in humans (Lee et al., 2008; Dohadwala et al. 2011 & Flammer et al. 2013). However, in vitro studies have purported that cranberry extract may be able to inhibit angiotensin-converting enzymes which might be able to lower blood pressure in humans (Apostolidis et. al., 2006)

Inflammation and Cranberry

The build-up of inflammation in the body has been linked to the formation of many diseases including cardiovascular and atherosclerosis which is an inflammatory disease (Mora et al., 2010). To this extent, researchers have become particularly interested in the study of cranberry juice consumption and its impact on inflammation in the body. Cranberry bioactives have been found to have a suppressing effect on the concentration of inflammatory cytokines in the body (Bodet et al., 2006; Huang et al. 2009).

In addition, studies in humans have provided evidence of cranberry’s anti-inflammatory effects on the body. One such research was that of Ruel et al (2008) who showed that the consumption of cranberry juice was observed to have reduced circulatory adhesion molecules in middle-aged men who led a sedentary lifestyle and thus would have risk factors for inflammation.

Another study by Zhu et al (2012) also showed a similar effect on inflammation with the consumption of a purified mixture of anthocyanins. However, a few other studies have failed to observe such results or any significant effects on some of the plasma markers of inflammation from the consumption of cranberry juice (Lee et al, 2008; Dohadwala et al. 2011; & Flammer et al. 2013; Basu et al., 2011).

Oral Health and Cranberry

Research has shown that cranberry juice may be effective in maintaining good oral health. This was observed in a double-blinded placebo-controlled study set up to assess the effects of cranberry on oral health. In this study, it was found that healthy persons who used a mixture of non-dialyzable material from cranberry as a daily mouthwash for six (6) weeks showed a significant reduction in the total bacterial count when compared to those who used a placebo mouthwash. However, the participants did not experience any changes in plaque or gingivitis indices (Weiss et al, 2004).

Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs) and Cranberry

Studies of the effect of Urinary tract infections (UTIs) and cranberry have been shaping the research debate for many years. It was one of the earliest researched topics due to the recurrent nature of UTIs and the repeated courses of antibiotics or treatment involved, sometimes on a long-term basis (Hooton, 2001) and the fact that this affects at least 60% of women at some stage during their lifetime (Foxman, 2002; Hooton, 2001; Russo, 2003).

While antibiotics have been proven as an effective treatment, these of course come with the noted side effects such as fungal super-infections or oral and vaginal thrush along with gastrointestinal infections (Albert et. al. 2004). However, the research on UITs and cranberry has been debatable in many circles due to inclusive findings when it comes to some research.

Many kinds of research have proven that the consumption of cranberry juice can be an effective alternative in helping with the prevention of UTIs. One such was a study conducted by Foxman et al (1995) with a group of Two Hundred and Eighty-eight (288) women with no history of UTIs. This research found that regular consumption of cranberry juice was associated with a lower risk of UTIs when compared to those who drank soft drinks, which had a higher odds ratio. However, it must be noted that these participants were cited as having to control their sexual activities throughout the research.

Similar results were also observed in a few double-blinded randomized placebo-controlled, crossover studies which assessed the antibacterial activity in the urine of humans after they consumed cranberry juice products or supplements. In one of the clinical trials with Eight (8) women, it was observed that there was a significant decrease in bacterial adherence to the human uroepithelial cells Twelve (12) hours after the consumption of cranberry in capsule form when compared with placebo (Lavign et al. 2008). The human uroepithelial or urothelial cells are a specialized type of cell that lines the inner surface of the bladder, ureters, and urethra (https://www.mypathologyreport.ca/).

Another study by Howell et. al., 2010) with Thirty-two (32) women, showed a significant dose-dependent reduction in bacterial adherence to human epithelial cells just after Twenty-four (24) hours after the consumption of cranberry powdered capsules when compared to placebo. The amount of cranberry powder taken for this study ranges anywhere from 0, 18, 36, or 72 mg/day. One of the downsides of this research was that the specific dosage that produced this result was not explicitly stated. Additionally, it must be noted that the urine of these women was analyzed ex vivo. An ex vivo analysis refers to an experiment that is conducted outside a living body.

Additionally, studies were also conducted with groups that had a history of recurrent UTIs. One such was conducted by Stothers (2002). This research was conducted with over One Hundred and Fifty (150) women who had a history of recurrent UTIs. The study found that fewer of the women experienced a recurrent UTI over 12 months when they consumed Seventy Hundred and Fifty millilitres (750 ml) of pure cranberry juice at Eighteen percent (18%) concentration or the same amount of cranberry concentration in tablet form. The research also showed that the juice lowered the incidences of recurrence of UTIs.

On the other hand, research conducted by Takahashi et al (2013) with Two Hundred Thirteen (213) women, did not observe any difference in UTI recurrence after the consumption of One Hundred and Twenty-five millilitres (125-ml) serving of cranberry juice or a placebo. The cranberry juice contained Forty (40 mg) of proanthocyanidins (PAC). However, this research was conducted over a 24-week period which was far less than the 12-month duration of Stother’s research. Additionally, it must be noted that proanthocyanidins are a specific type of polyphenol found in cranberries.

As such, while some research has found favourable associations between the consumption of cranberry juice and the incidences of UTIs, others are inconclusive or show no effect. Nonetheless, sufficient research has observed and contends that cranberry juice can be used as a complement to the prevention of UTIs along with a healthy diet.

The degree of impact, however, as seen based on research, will be dependent on many factors including, the amount of cranberry juice consumed as well as the duration among other lifestyle factors. As such, if you believe you have a UTI, it would be recommended that you see a healthcare professional for diagnosis and treatment. Do not just use cranberry products to treat any such condition.

Are there any side effects of consuming too much cranberry juice?

Too much of anything is never a good thing, even if it is considered healthy. However, controlled clinical pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic studies have shown no clinically relevant side effects or interactions with the consumption of cranberry juice. As such, it is considered safe for most persons.

However, some research has shown that it might interact with warfarin particularly if consumed in high amounts such as Three Thousand milligrams (3000 mg) or more of encapsulated cranberry juice concentrate. Warfarin is a medication that is typically prescribed for the prevention of blood clots.

On the other hand, other studies have shown no interaction with warfarin, while others have shown low interaction (Lilija et al. 2007, Li et al. 2006, Ansell, 2009). Additionally, some studies have shown that drinking too much cranberry juice (no definition for ‘too much’ was established) may cause mild stomach upset or even diarrhea in some persons (webmd.com). Additionally, drinking more than a litre of cranberry juice daily and over an extended period could increase on chances of developing kidney stones (webmd.com).

Therefore, it is always best to stay on the side of caution and consult with your medical professional if you are planning on taking cranberry products as part of a supplement regimen, especially, if you are on medications. Additionally, it is also recommended that one consume water after drinking cranberry juice, due to its acidic nature.

Illustrative Summary

Here is a summary of the Five (5) ‘must know’ health benefits of Cranberry Consumption.

Let’s Sum Up!

Cranberry and its effects on human health have long been studied for years with much-reported success in many of the studies. These little red berries are purported to be a rich source of dietary nutrients including phenolic bioactive, flavonoids, vitamin C, and catechins as well as a unique profile of anthocyanins. However, it is relatively low in natural sugars hence, its characteristic tart and astringent taste.

Cranberries are enjoyed in many forms such as in sauces and dried fruits with the most popular being as a juice. It is also available in supplement forms including capsules, tablets, and loose powder. However, most research has been concentrated on the effects of its juice and or supplements particularly, those in the form of capsules or powdered on human health, particularly on urinary tract infections (UTIs).

Some of the other benefits of cranberry juice consumption include its potential in lowering low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol while increasing high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol and thus one’s overall cardiovascular health. It is also reportedly capable of reducing high blood pressure and inflammation in the body.

Another benefit cited by research is its benefits on oral health, which observed it being able to help reduce bacterial count when used as a mouthwash. Last, but certainly not least, is its impact on urinary tract infections (UTIs) particularly in their prevention or recurrence.

While more research is needed in some of the cases to fully understand the mechanism of action for the favourable effects on human health, other findings have been debatable or inclusive, especially as it relate to UTIs. However, the degree of its success will be dependent on dosage, format, and duration to produce the optimal results.

Additionally, the type of individual that may experience the most benefits is also a limitation of some of the studies as some have shown no particular effects on healthy individuals. Nonetheless, from the research that has been published, it can be affirmed that cranberries can contribute positively to one’s overall health and should therefore be considered a unique part of a healthful diet. Further, if you suspect that you have a UTI, it is recommended that you visit your healthcare provider for diagnosis and treatment.

So, with all that was said, will cranberries become a staple or a foe in your health and wellness journey? Well, for me, it will remain a staple.

You can read more on vitamins and minerals here as well as on another famous berry here.

- Our ABCs (Vitamin Overview)

- Blueberries – They are more than just for brain health – Here are 5 awesome benefits worth knowing!

Editor’s Note: Article was updated on July 11, 2024.

- Albert X, Huertas I, Pereiro, Sanfelix, II J, Gosalbes V, Perrota C. Antibiotics for preventing recurrent urinary tract infection in nonpregnant women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(3):CD001209.

- Ansell J, McDonough M, Yanli Z, Harmatz J, Greenblatt, D. The absence of an interaction between warfarin and cranberry juice: A randomized, double-blind trial. J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;49:824-30.

- Apostolidis E, Kwon YI, Shetty K. Potential of cranberry-based herbal synergies for diabetes and hypertension management. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2006;15:433–41.

- Basu A, Betts NM, Ortiz J, Simmons B, Wu M, Lyons TJ. Low-energy cranberry juice decreases lipid oxidation and increases plasma antioxidant capacity in women with metabolic syndrome. Nutr Res. 2011;31:

- 190–6.

- Blumberg, J. B., Camesano, T. A., Cassidy, A., Kris-Etherton, P., Howell, A., Manach, C., Ostertag, L. M., Sies, H., Skulas-Ray, A., & Vita, J. A. (2013). Cranberries and their bioactive constituents in human health. Advances in nutrition (Bethesda, Md.), 4(6), 618–632. https://doi.org/10.3945/an.113.004473

- Bodet C, Chandad F, Grenier D. Anti-inflammatory activity of a highmolecular- weight cranberry fraction on macrophages stimulated by lipopolysaccharides from periodontopathogens. J Dent Res. 2006;85: 235–9.

- Bruyere F. [Use of cranberry in chronic urinary tract infections]. Med Mal Infect. 2006;36(7):358-63, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.medmal.2006.05.001.

- Chu YF, Liu RH. Cranberries inhibit LDL oxidation and induce LDL receptor expression in hepatocytes. Life Sci. 2005;77:1892–901.

- Dohadwala MM, Holbrook M, Hamburg NM, Shenouda SM, Chung WB, Titas M, Kluge MA, Wang N, Palmisano J, Milbury PE, et al. Effects of cranberry juice consumption on vascular function in patients with coronary artery disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93:934–40.

- Foxman B, Geiger AM, Palin K, Gillespie B and Koopman JS. First-time urinary tract in-fection and sexual behavior. Epidemiology. 1995;6:162-8.

- Foxman B. Epidemiology of urinary tract infections: incidence, morbidity, and economic costs. Am J Med. 2002;113 Suppl 1A:5S-13S.

- Flammer AJ, Martin EA, Gossl M, Widmer RJ, Lennon RJ, Sexton JA, Loeffler D, Khosla S, Lerman LO, Lerman A. Polyphenol-rich cranberry juice has a neutral effect on endothelial function but decreases the fraction of osteocalcin-expressing endothelial progenitor cells. Eur J Nutr. 2013;52:289–96.

- Guay DR. Cranberry and urinary tract infections. Drugs. 2009;69(7):775- 807, http://dx.doi.org/10.2165/00003495-200969070-00002.

- Hisano M, Bruschini H, Nicodemo AC, Srougi M. Cranberries and lower urinary tract infection prevention. Clinics. 2012;67(6):661-667. Received for publication on December 1, 2011; First review completed on January 6, 2012; Accepted for publication on February 13, 2012.

- Hooton TM. Recurrent urinary tract infection in women. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2001;17(4):259-68, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0924-8579(00) 00350-2.

- Howell AB, Botto H, Combescure C, Blanc-Potard A-B, Gausa L, Matsumoto T, Tenke P, Sotto A, Lavigne JP. Dosage effect on uropathogenic Escherichia coli anti-adhesion ac-tivity in urine following consumption of cranberry powder standardized for proanthocya-nidin content: a multicentric randomized double blind study. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:94.

- Huang Y, Nikolic D, Pendland S, Doyle BJ, Locklear TD, Mahady GB. Effects of cranberry extracts and ursolic acid derivatives on P-fimbriated Escherichia coli, COX-2 activity, pro-inflammatory cytokine release

- and the NF-kappa beta transcriptional response in vitro. Pharm Biol. 2009;47:18–25.

- Kalgaonkar S, Gross HB, Yokoyama W, Keen CL. Effects of a flavonolrich diet on select cardiovascular parameters in a Golden Syrian hamster model. J Med Food. 2010;13:108–15.

- Lavigne JP, Bourg G, Combescure C, Botto H, Sotto A. In-vitro and in-vivo evidence of dose-dependent decrease of uropathogenic Escherichia coli virulence after consumption of commercial Vaccinium macrocarpon (cranberry) capsules. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008;14(4):350-355.

- Lee IT, Chan YC, Lin CW, Lee WJ, Sheu WH. Effect of cranberry extracts on lipid profiles in subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2008;25:1473–7.

- Li Z, Seeram NP, Carpenter CL, Thames G. Cranberry does not affect prothrombin time in male subjects on warfarin. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106:2057-61.

- Lilja JJ, Backman JT, Neuvonen PJ. Effects of daily ingestion of cranberry juice on the pharmacokinetics of warfarin, tizanidine, and midazolam—probes of CYP2C9, CYP1A2, and CYP3A4. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007;81:833-9.

- Mora S, Glynn RJ, Hsia J, MacFadyen JG, Genest J, Ridker PM. Statins for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events in women with elevated high-sensitivity C-reactive protein or dyslipidemia: results

- from the Justification for the Use of Statins in Prevention: An Intervention Trial Evaluating Rosuvastatin (JUPITER) and metaanalysis of women from primary prevention trials. Circulation. 2010;121:1069–77.

- Qin Y, Xia M, Ma J, Hao Y, Liu J, Mou H, Cao L, LingW. Anthocyanin supplementation improves serum LDL- and HDL-cholesterol concentrations associated with the inhibition of cholesteryl ester transfer

- protein in dyslipidemic subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:485–92.

- Ruel G, Pomerleau S, Couture P, Lamarche B, Couillard C. Changes in plasma antioxidant capacity and oxidized low-density lipoprotein levels in men after short-term cranberry juice consumption. Metabolism. 2005;54:856–61.

- Ruel G, Pomerleau S, Couture P, Lemieux S, Lamarche B, Couillard C. Favourable impact of low-calorie cranberry juice consumption on plasma HDL-cholesterol concentrations in men. Br J Nutr. 2006;96: 357–64.

- Ruel G, Pomerleau S, Couture P, Lemieux S, Lamarche B, Couillard C. Low-calorie cranberry juice supplementation reduces plasma oxidized LDL and cell adhesion molecule concentrations in men. Br J Nutr.

- 2008;99:352–9.

- Russo TA, Johnson JR. Medical and economic impact of extraintestinal infections due to Escherichia coli: focus on an increasingly important endemic problem. Microbes Infect. 2003;5(5):449-56, http://dx.doi.org/

- 10.1016/S1286-4579(03)00049-2.

- Stothers L. A randomized trial to evaluate effectiveness and cost effectiveness of naturo-pathic cranberry products as prophylaxis against urinary tract infection in women. Can J Urol. 2002:9:1558-62.

- Takahashi S, Hamasuna R, Yasuda M, Arakawa S, Tanaka K, Ishikawa K, Kiyota H, Hayami H, Yamamoto S, Kubo T, Matsumoto T. A randomized clinical trial to evaluate the preventive effect of cranberry juice (UR65) for patients with recurrent urinary tract infec-tion. J Infect Chemother. 2013;19:112-7.

- Tall AR. CETP inhibitors to increase HDL cholesterol levels. N EnglJ Med. 2007;356:1364–6.

- Weiss EI, Kozlovsky A, Steinberg D, Lev-Dor R, Bar Ness Greenstein R, Feldman M, Sharon N, Ofek I. A high molecular mass cranberry constituent reduces mutans strepto-cocci level in saliva and inhibits in vitro adhesion to hydroxyapatite. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2004;232:89-92.

- Yung LM, Tian XY, Wong WT, Leung FP, Yung LH, Chen ZY, Lau CW, Vanhoutte PM, Yao X, Huang Y. Chronic cranberry juice consumption restores cholesterol profiles and improves endothelial function in ovariectomized rats. Eur J Nutr. 2013;52:1145–55.

- Zhao, Shaomin & Liu, Haiyan & Gu, Liwei. (2018). American Cranberries and Health Benefits – an Evolving Story of 25 years. Journal of the science of food and agriculture. 100. 10.1002/jsfa.8882.

- Zhu Y, Ling W, Guo H, Song F, Ye Q, Zou T, Li D, Zhang Y, Li G, Xiao Y, Liu F, Li Z, Shi Z, Yang Y. Anti-inflammatory effect of purified dietary anthocyanin in adults with hypercholesterolemia: a randomized controlled trial. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2013 Sep;23(9):843-9. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2012.06.005. Epub 2012 Aug 17. PMID: 22906565.